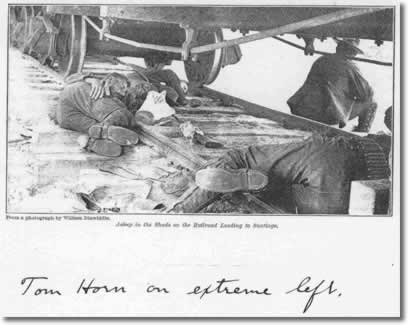

This post is a part of our series on Tom Horn – full collection of links at the bottom of the page.

“The two men, being of the same character and same plane of living, of course they had trouble.” -Glendolene Myrtle Kimmell

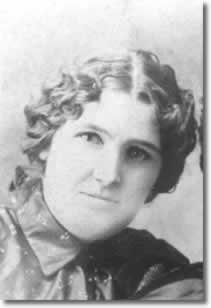

Glendolene Myrtle Kimmell had come to Wyoming to teach school early in 1901 from Hannibal, Missouri. Hannibal is near the location of Tom Horn’s birth in Scotland County in the northeastern part of the state.

She was born on June 21, 1879 in St. Louis. Her mother, Frances “Fannie” Ascenath Pierce Kimmell, was born in Hannibal in 1843. Frances was one of ten children in a socially prominent family. In July 1864 she married Elijah Lloyd Kimmell, whom she met in St. Louis where he was working for a railroad. Elijah was born in Williams Center, Ohio in 1842 and was a Civil War veteran.

One of Frances’ brothers, Glendolene’s Uncle Edward Pierce, was a playmate of Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain. The Pierce family home at 321 North Fifth Street in Hannibal was only a block from Clemens’ boyhood home.

Glendolene had two siblings, John Pierce Kimmell, who was born in 1865 and died March 23, 1882. Daisy Natalie Kimmell, who was born in 1870, died June 27, 1872.

Elijah Kimmell died in 1881 in St. Louis. Glendolene, her brother and mother moved back to the family home in Hannibal upon his death. Both of Glendolene’s parents and siblings are buried in Hannibal.

Glendolene’s name first appears in the Hannibal city directory in 1895 and 1897-1898. (Directories were not printed every year.)

Physically small in size in adulthood, she was estimated to be only four and one-half feet tall.

She was one of a group of young women recruited to teach in the West at the turn of the century. On her way to Wyoming it is believed she visited an uncle, Charles Pierce, who was working for a railroad and living in Jamestown, North Dakota. She arrived in Wyoming early in 1901.

Tom Horn’s comments in his so-called confession that Glendolene was of mixed blood, possibly having a Hawaiian or Polynesian ancestry, were stimulated by alcohol and his imagination. He added that she “spoke most every language on earth.” She denied the ancestry and language comments and said, in the affidavit she filed as part of the appeals to the acting governor to commute Horn’s death sentence, that if she spoke many languages that she would not have been teaching school in Iron Mountain, Wyoming.

She authored a lengthy document in Denver in April 1904 that was printed in the appendix to Tom Horn’s autobiography. In it she said that part of her reasoning for coming to the West and to teach at the Miller-Nickell school was that she had “been most strongly attracted by the frontier type. I was happy in the belief that I would meet with the embodiment of that type… [but] I was doomed to disappointment, for all the cattle men and cow boys I saw were like the hired hands ‘back East.’”

In contrast, her description of Horn is different: “…there stopped at the Miller ranch a man who embodied the characteristics, the experiences of the old frontiersman.”

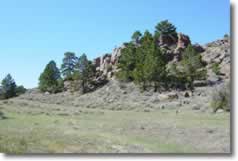

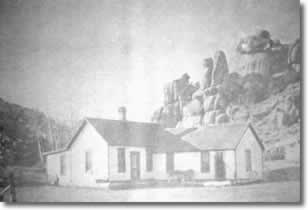

Kimmell had been warned against going to the Miller-Nickell school because of the feud between the two families. However, she entered into an agreement to teach at the school and to board at Miller’s ranch with her eyes wide open. She stated in the inquest into Willie Nickell’s death that she felt the experience would give her a better understanding of human nature.

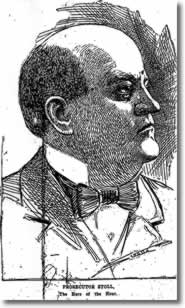

Her testimony in the coroner’s inquest further reflect feelings of disdain toward the homesteaders. Under questioning by the district attorney, Walter R. Stoll, she confirmed the events of July 15-August 4, and provided her own reasons why Kels Nickell and Jim Miller were inevitably bound to clash.

The first part of her testimony in response to questions by the prosecutor covered the happenings at Miller’s ranch when they learned of Kels being shot on Sunday, August 4.

KIMMELL. Well, Sunday morning I didn’t leave my room until twenty minutes past nine. The occasion for my leaving then was that Gus Miller came into the front room just next to mine and announced to his father that Nickell had been shot….

STOLL. Up to that time, that is when you went into the room, upon hearing what Gus had said, you hadn’t seen any of the Miller family that morning?

KIMMELL. Yes, I had seen Victor.

STOLL. Where and when had you seen him?

KIMMELL. I looked out of the window of my room about half past eight and saw him….

STOLL. Had you seen any other members of the family?

KIMMELL. I saw some of the little children playing about but none of the older members.

STOLL. Do you know anything about any of the older members being about the house previous to this time?

KIMMELL. I woke up the first time at five o’clock; everything in the house was still…. At seven o’clock I heard Mr. Miller in the front room just off of mine….

STOLL. How do you know it was Mr. Miller?

KIMMELL. He was passing back and forth, and singing….

STOLL. How do you know whether Mr. Miller and Mrs. Miller occupied the same room the night before?

KIMMELL. I don’t know about that night.

STOLL. Is it their general habit to occupy separate rooms?

KIMMELL. Mr. Miller has a room by himself and Mrs. Miller has a room with some of the children….

This essay was originally published on Chip Carlson’s personal website, which has since expired, and is re-published here as a way to preserve some of the content of this historical figure. If you would like to continue learning about Tom Horn, please explore the links below. If you’d like to read the complete story, and help to support the author, his book can be purchased here.

More about Tom Horn:

Tom Horn (main page)

The Tom Horn Story (summary)