This post is a part of our series on Tom Horn – full collection of links at the bottom of the page.

“That’s the man that killed Daddy.”

William Lewis was not the last name tied to killings allegedly carried out by Tom Horn.

The second homesteader to be killed was Fred U. Powell. Old timers have argued whom deserved killing more, Lewis or Powell, and Powell is usually the choice. There was a reason for it, simply that he got into more trouble with more people. It seemed that during his entire tenure in Wyoming he went out of his way to find trouble, and perhaps trouble found a way to find him.

Powell was born in Virginia and became well known in the area virtually from the time of his arrival in the mid-to-late 1870s, simply because he seemed to want to become a sort of pariah in southeast Wyoming. He had married Mary Keene in December 1882, the daughter of John and Mary Keene, well?known pioneers who had come to Laramie from Colorado in 1868.

Fred and Mary had a son, William E. “Billy,” who was five years old when he supposedly witnessed his father’s murder on September 10, 1895. Fred was only thirty-seven at the time of his death.

T. Blake Kennedy, who became a key player on Tom Horn’s legal defense team and later a U.S. District Judge, mentioned in his memoirs, “It had been reported that at a coroner’s [Powell’s] inquest the small son of the murdered man, who was perhaps five years old, made the remark in identifying Horn, ‘That’s the man that killed Daddy.’”

Fred had lost an arm in an accident working for the Union Pacific, and was given a job as a night watchman with the railroad before being fired for robbing a traveler (probably a drifter), who was working his way across the country, of twenty dollars.

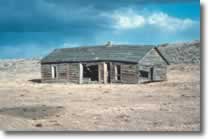

He then took up ranching on the west side of the Laramie Range in Albany County, upstream on Horse Creek about seven miles southwest of the spot where William Lewis had been shot. He became proficient with a rope and horse in spite of his handicap, and was generally considered a rustler. Supposedly he was the only person in the area who was friendly with Lewis. Fred, however, was in most ways an anathema to the ranching community and even the populace in general because of his continuing propensity to steal, trespass and destroy property. He thought it was fun to taunt his neighbors – in a manner he felt was more humorous than did they – with invitations to have their own beef for dinner at his place.

The charges leveled against him read like a sad litany to his seemingly endless pursuit of breaking the law. From pre-statehood days before 1890, they read like a self-defeating chant:

Territory of Wyoming v Fredrick U. Powell, Stealing and Killing Neat Cattle, Albany County

State of Wyoming…Grand Larceny, Cheyenne Justice of the Peace

State of Wyoming… Stealing Live Stock, Albany County

State of Wyoming… Malicious Trespass and Destruction of Property, Albany County

State of Wyoming… Incendiarism and Malicious Trespass, Albany County

State of Wyoming… Criminal Trespass, Albany County

First he stole four horses in Albany County in July 1889. He was arrested and jailed in September, and after the grand jury held its proceedings, the charges were dropped and he was never brought to trial.

In August 1890 he was charged with grand larceny in Cheyenne. The justice of the peace sustained a motion by Powell’s lawyer that there was not enough evidence to show any crime had been committed, and Fred was released.

In January 1892 Mary Powell filed for divorce on grounds that for seven years he had not supported her or their son, who was then seven. The divorce was granted the next month. Mary however continued to live with Fred for years after that, although perhaps on an intermittent basis.

The summer after the divorce he was charged with stealing a horse in Albany County. Fred pleaded not guilty, and after four days of legal arguments he was bound over for trial. At the trail in September the jury returned with a verdict of not guilty.

In July the next year Fred was charged with malicious trespass and destroying fences belonging to Etherton P. Baker. First he was convicted but filed an appeal, and in September the jury found him not guilty.

That was not the last Fred U. Powell had heard from Etherton P. Baker, however.

The next spring, in April 1894, he set fire to personal property belonging to Baker and another neighbor, Joseph Trugillo, who was apparently living with Baker. Powell was hauled into court but this was not to be his figurative best day in court. He appealed the light sentence that was meted out and was released on a hundred-dollar bond.

In July Powell stole a horse, was arrested and tried. The judge found him guilty and fined him forty-five dollars. Again he appealed and was released on bond. When the next trial for incendiarism came up in September, he was convicted and sentenced to four months in jail. The charges were dropped in the horse-stealing charge.

When Powell was released in early 1895 he started to receive letters. The letters bore the now-familiar theme to stop stealing, leave the country or be killed. For a while he seemed to disregard them, at least until William Lewis was murdered.

There were reports that the Lewis murder threw a fright into him, and he started selling his stock.

Powell met the same fate as Lewis the morning of September 6, 1895….

This essay was originally published on Chip Carlson’s personal website, which has since expired, and is re-published here as a way to preserve some of the content of this historical figure. If you would like to continue learning about Tom Horn, please explore the links below. If you’d like to read the complete story, and help to support the author, his book can be purchased here.

More about Tom Horn:

Tom Horn (main page)

The Tom Horn Story (summary)